Human evolution: a one-million-year clusterf**k

A new incredibly subtle and elegant analysis of our living genomes reveals yet another major piece in the jigsaw of human evolution, completely hidden until now.

We are an African species. This is often said, but I think needs some unpacking. In its simplest form, it means that Homo sapiens, the species to which we assign ourselves, emerged from earlier forms of hominids within the last 400,000 years or so, and subsequently populated every corner of the world. Most of that evolution occurred in what is now Africa, though regional adaptations and superficial yet visibly different traits came later as a small proportion of people left that continent and slowly migrated around the planet.

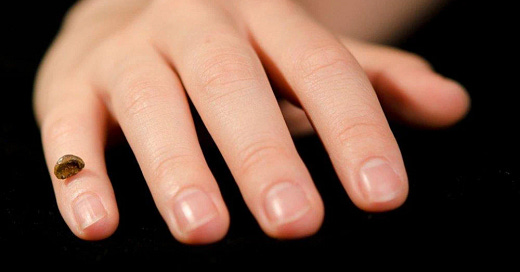

Other types of humans existed, but we are the last. I, though not all agree, refer to humans as members of the great ape genus Homo, therefore including our European ancestors Homo neanderthalensis, our upstanding global cousins Homo erectus, their hobbity island relatives Homo floresiensis, and a handful of others. Another member of our extended clan turned up in 2008, when a single finger bone and a large molar of a teenage girl were found in a cave in Siberia that had once been occupied by a Christian eremite called Denis. Hence, she was placed in a new category called the Denisovans (pron: den-nees-o-vans). Species are generally designated by morphology, and her sparse physical remains are not enough to place the Denisovans in a new species category. But it was enough to get DNA out of that little finger, and with that, to say that her people were not the same as Neanderthals (but closely related to them), and not the same as us. With her ancient DNA known, we can also say with confidence that bits of her genome reside in many people of east Asian descent today, just as the DNA of Neanderthals nestles happily within the genomes of people of Eurasian descent. They were not our evolutionary cousins, but our ancestors.

We use a lot of jargon in evolutionary genetics – admixture, gene flow events – but really they are technical euphemisms for sex. For a long time, our species and its near relatives have been very successful in two domains: moving and sex. Over evolutionary time periods, populations are never static, either geographically or with whom they shag, but we strive to describe discrete groups of people in order for us to understand our deep history. The arrival of ancient DNA on the scene about 15 years ago upturned our ability to understand just who was shagging who the gene flow events hundreds of thousands of years ago, and in doing so, deciphering the evolution of us who remain.

A few years ago, I was struggling to find a metaphor to describe this evermore complex picture, and I stumbled upon the coinage of American counterculture legend Edward Sanders to describe a chaotic situation in the military. But I think it’s much more apposite here: instead of the nice, neat branching tree of life, human evolution is much more like a one big, million-year clusterfuck.

Until this century, the oldest members of our species had been found in east Africa, but new dating of old bones found in Morocco pushed back the date to more than 300,000 years, and in the north of Africa. What began to emerge was a model of the emergence of Homo sapiens as a kind of gestalt, pan-African species. Weak yet high-profile studies tried to pin down a specific location, but that’s not really how evolution works, and I and others robustly debunked those claims.

Anyway. This week, Trevor Cousins, Aylwyn Scally and Richard Durbin dived further into the orgy. In a brilliant new paper, they use a new computational technique to detect the finest of traces of much deeper African history. They looked at the publicly available human genomes, and applied a hidden Markov model, which is a statistical method for detecting extremely subtle patterns in observable data. In this case, the data are the genomes of living people.

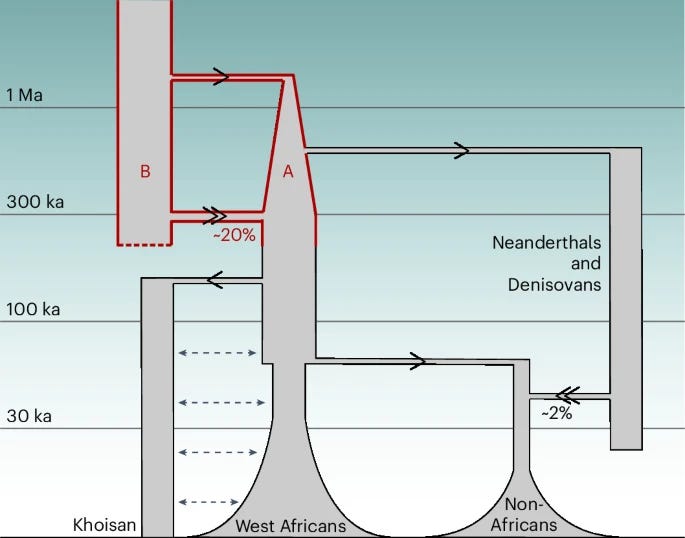

Broadly, the picture revealed is that a population of unknown humans in Africa split in two around 1.5 million years ago, separated, and did not interbreed again until around 300,000 years ago. It is this union from which Homo sapiens emerges. It was not an even merger: one population makes up about four fifths of the fusion.

A quote from the paper:

‘in the last tens of thousands of years, there has been repeated separation and subsequent remixing, or admixture, of populations.’

I love the use of the word remixing there. Technically they mean they ‘mixed again’, but what is remixing in its modern sense if not the creation of something new from two or more things that were previously separate?

Really cool side note: the analysis also suggests that the population from whom both Neanderthals and Denisovans emerged came only from the majority group. Some of them split in the time before the remixing that gave us us, and slowly migrated out of Africa. They would not meet Homo sapiens for more than half a million years. As soon as they did, genes flowed. And that is why you (if you have European ancestry) carry Neanderthal DNA.

The question that emerges, and is as yet unanswerable, is who were these populations?

Though extremely powerful as a source text, aDNA is not well preserved in hotter climates, and over very long periods of time, so we do not have DNA from dead people that long ago. Therefore, we cannot, and may never be able to absolutely say who the two populations that gave rise to us (one of which gave rise to the Neanderthals and Denisovans) actually were. We may know them already, perhaps Homo heidelbergensis, or a Homo erectus? But we cannot get DNA out of those bones to check.

We would also like to know why they split. One population became two, stayed apart for more than a million years, and then got back together again. Why?

So, yet again, the genetics provides clues that are unavailable in the bones. This is not to disparage palaeoanthropology. These are complementary fields, and the job is to resolve the evidence of both. Chris Stringer, the doyen of human evolution commented that ‘the results are very challenging for those of us working with human fossils’. That is a good thing.

One thing that these results clearly show is that once again, the metaphor of evolution as a branching tree is entirely unsatisfactory. Perhaps streams and rivulets flowing through oceans of time is better. Some streams diverge forever, some peter out. Others separate but flow back into one other and reform a more robust river, and eventually coalesce into the only human estuary that remains, which is us. Just as with historical family trees, they are intricate, complex, messy and not at all like trees. Those days where we confidently represented human evolution as the hideous inevitable March of Progress are long gone, and good riddance to bad metaphors. I much prefer a clusterfuck.

The music "remix" metaphor seems very appropriate - musical styles evolve independently - with many offshoots that peter out - then occasionally crash together to dominate for a while...

Excellent piece, thanks for sharing!